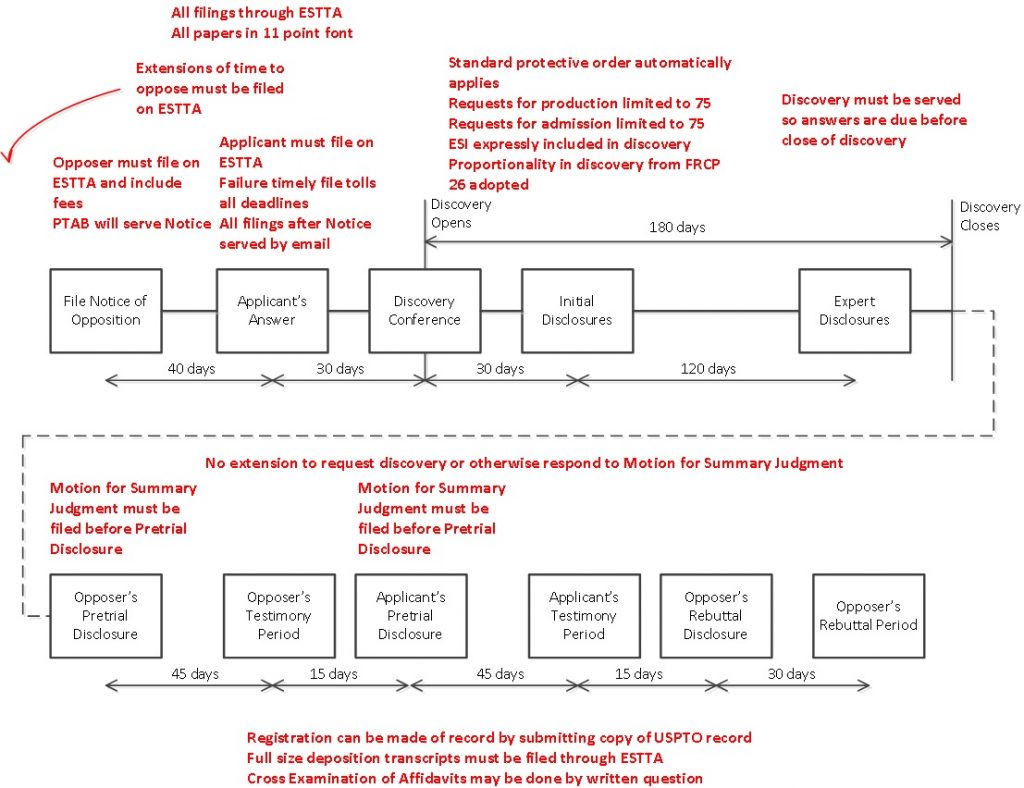

The USPTO has amended the rules for TTAB proceedings. A Notice of Final Rulemaking was published in the Federal Register on October 7, 2016. The effective date of the amended rules is January 14, 2017. The amended rules are applicable to all cases pending on January 14, 2017 as well as those cases commenced on or after January 14, 2017. The USPTO published a table summarizing the amendments is posted. The impact of the new rules on Oppositions is summarized on this chart:

Author Archives: bwheelock

I ♥ TTAB

In D.C. One Wholesaler, Inc. v. Chien, [Opposition No. 91199035/Cancellation No. 92053919](TTAB October 4, 2016), the TTAB was called upon to resolve a dispute over the ownership of the trademark I ♥ DC. The TTAB held in a non-precedential opinion, that I ♥ DC was not a trademark — not for being deceptively misdescriptive, as one might expect, but simply because it did not function as a mark.

The TTAB reminded us that the Trademark Act is not an act to register mere words, but rather to register trademarks. The Board said that before there can be registration, there must be a trademark, and unless words have been so used they cannot qualify. The Board found that the record before it indicated that I ♥ DC has been widely used, over a long period of time and by a large number of merchandisers, as an expression of enthusiasm, affection or affiliation with respect to the city of Washington, D.C. The Board further found that the marketplace is awash in products that display the term I ♥ DC as a prominent ornamental feature of such goods, in such a way that the display itself is an important component of the product and customers purchase the product precisely because it is ornamented with a display of the term.

The Board concluded:

We find that the phrase I ♥ DC on apparel and other souvenirs, whether displayed in the stacked format shown in the Registration or in the horizontal format shown in the Application, would be perceived by purchasers and prospective purchasers as an expression of enthusiasm for the city of Washington, DC. Under such circumstances, customers would not perceive I ♥ DC as an indicator of the source of the goods on which it appears.

Thus, the Board held that I ♥ DC fails to function as a trademark. The Board sustained the opposition, and cancelled Opposer’s registration.

The Board’s decision is non-precedential, perhaps because the Board did not want to to encourage a close look into the many registered trademarks that function like I ♥ DC. When someone buys a shirt or other trinket with a short sentiment (or even a sports team name) do they really think about, or even care about, the source? In the vast majority of cases they couldn’t care less about the source, they are buying the message. Ever since Dallas Cap & Emblem, the dirty little secret of trademark law is that we routinely bend trademark protection to protect the message and not the source. However, when you bend trademark law too far, it occasionally snaps.

A Mark Should be Considered a Whole, and not Dissected

In Oakville Hills Cellar, Inc. v. Georgallis Holdings, LLC, [2016-1103] the Federal Circuit affirmed the TTAB’s finding that Oakville’s registered mark MAYA and Georgallis’s applied-for mark MAYARI are sufficiently dissimilar.

The Federla Circuit expalined that the likelihood of confusion analysis considers

all DuPont factors for which there is record evidence but may focus on dispositive factors, such as similarity of the marks and relatedness of the goods.

Oakville complained that the Board overlooked record evidence of the marks’ similarities in appearance, pronunciation, meaning, and overall commercial impression. Oakville argued that MAYA dominated both marks, and that the suffix -RI in MAYARI is of minor import as a distinguishing element, particularly with the registered mark MAYA entirely subsumed within the leading portion of MAYARI, which could cause confusion.

Georgallis responds that the Board correctly declined to dissect MAYARI into MAYA and RI, an element with no meaning, and instead found that consumers would perceive MAYARI as a unitary whole and a coined term. According to Georgallis, the Board properly considered the marks in their entireties and found that MAYA is familiar to U.S. consumers as a reference to the Mayan culture and as a popular female given name, whereas MAYARI is unfamiliar to U.S. consumers.

The Federal Circuit concluded that substantial evidence supports the

Board’s finding that the marks were sufficiently dissimilar as to appearance, sound, meaning, and commercial impression. The Federal Circuit said that in determining similarity or dissimilarity, the marks must be compared in their entireties. The Federal Circuit said that Board properly found that there is insufficient evidence that consumers would perceive MAYARI as MAYA- and -RI, agree with the Board that the letters RI, alone, have no relevant meaning, and provide no reason for a customer to view the mark logically as MAYA plus RI, rather than as a single unitary expression. The Federal Circuit said that there no reason to break the term into MAYA-RI than MAY-ARI or MA-YARI.

The Federal Circuit said that a single DuPont factor may be dispositive in a likelihood of confusion analysis, especially when that single factor is the dissimilarity of the marks. The Federal Circuit affirmed the decision of

the Board dismissing Oakville’s opposition.

Federal Circuit Skewers Trademark Applicant

In In re Cordua Restaurants, Inc., [2015-1432] (May 13, 2016), the Federal Circuit affirmed the refusal of registration of the stylized mark CHURRASCOS for restaurant services on the ground that term is generic.

Applicant operated a chain of restaurants branded as Churrascos, serving a variety of South American dishes, including grilled meats, including a signature “Churrasco Steak.” Applicant applied and obtained Reg. No. 3,439,321 on CHURRASCOS for “restaurant and bar services; catering.” However, the Examiner refused registration on the stylized version of CHURRASCOS because it “refer[s] to beef or grilled meat more generally” and that the term “identifies a key characteristic or feature of the restaurant services, namely, the type of restaurant.” The Board affirmed the refusal.

The Federal Circuit said that a generic term ‘is the common descriptive name of a class of goods or services, and that the critical issue in genericness cases is whether members of the relevant public primarily use or understand the term sought to be protected to refer to the genus of goods or services in question. Genericness is determined according to the two-step Ginn test: First, what is the genus of goods or services at issue? Second, is the term sought to be registered or retained on the register understood by the relevant public primarily to refer to that genus of goods or services?

Cordua argued that the Board misapplied the first step in focusing on its specific type of services, rather than on the broader description of services in the application, While agreeing that the focus should be on the description as set forth in the application, saying the correct question is not whether “churrascos” is generic as applied to Cordua’s own restaurants but rather whether the term is understood by the restaurant-going public to refer to the wider genus of restaurant services. However, the Federal Circuit found that the Board’s apparent error in considering Cordua’s own restaurant services is harmless, because in the end the Board focused on “restaurant services.” As to the second step of the Ginn test, the Federal Circuit found substantial evidence supported the finding that churrascos is the generic term for a type of cooked meat, and for a restaurant featuring churrasco steaks.

The Federal Circuit rejected Cordua’s argument that the “s” on the end of CHURRASCO made the term non-generic, because CHURRASCOS is not the proper plural of CHURRASCO, while the Federal Circuit countered that “pluralization commonly does not alter the meaning of a mark.” Since “churrascos” is an English-language term, there is nothing in the record to indicate that the addition of the “S” at the end alters its meaning (beyond making the word plural).

The Federal Circuit said its precedent makes clear that a term is generic if the relevant public understands it to refer to a key aspect of the genus of goods or services in question. The Federal Circuit said that there is substantial evidence in the record that “churrascos” refers to a key aspect of a class of restaurants because those restaurants are commonly referred to as “churrasco restaurants.”

Finally the Federal Circuit noted that stylized nature of the mark cannot save it from ineligibility as generic

New Year’s Resolution for a BRAND New Year

A new year is upon us, and we suggest that trademark owners make it a brand new year, by resolving to use their marks correctly going forward. Proper trademark use is important to creating and maintaining trademark rights, and the rules are relatively simple — just follow the ACID test: Adjective, Consistent, Identified, and Distinctive.

A mark is an adjective identifying a particular kind of product or service, and it should be used as such. A trademark should be paired with a generic term for the product or service. “Buy an ACME™ widget.” is preferred over “Buy an ACME™.”

A mark should be used consistently so that it is more readily recognized by consumers. In Reebok International Ltd. v. Kmart Corp., 849 F.Supp. 252, 31 USPQ2d 1882 (S.D.N.Y. 1994), the Court noted the limitations on the strength of Reebok’s trade dress “because Reebok has used the Stripecheck inconsistently.”

A mark should be identified as a mark and not a normal word. Registered marks should be identified with the ® symbol, and unregistered marks with a ™. This is pretty straight-forward, but many trademark owners drop the ball when the mark appears multiple time on a package or advertisement. Should the mark be identified every time it appears? Yes is should. However at the very least the most prominent use of the mark should be identified on every “sight” – each page or each face of the package. That way every one encountering the mark will be apprised of its trademark status.

Finally, the a mark should be used distinctively. The mark should stand out from other words in an advertisement or on a package. The mark should be bigger or bolder or in color. Anything that draws attention to the fact that the mark is special.

Applying the ACID test to your trademark use will help you build and maintain strong trademark rights. This year resolve to use your marks properly, and make this a BRAND new year!

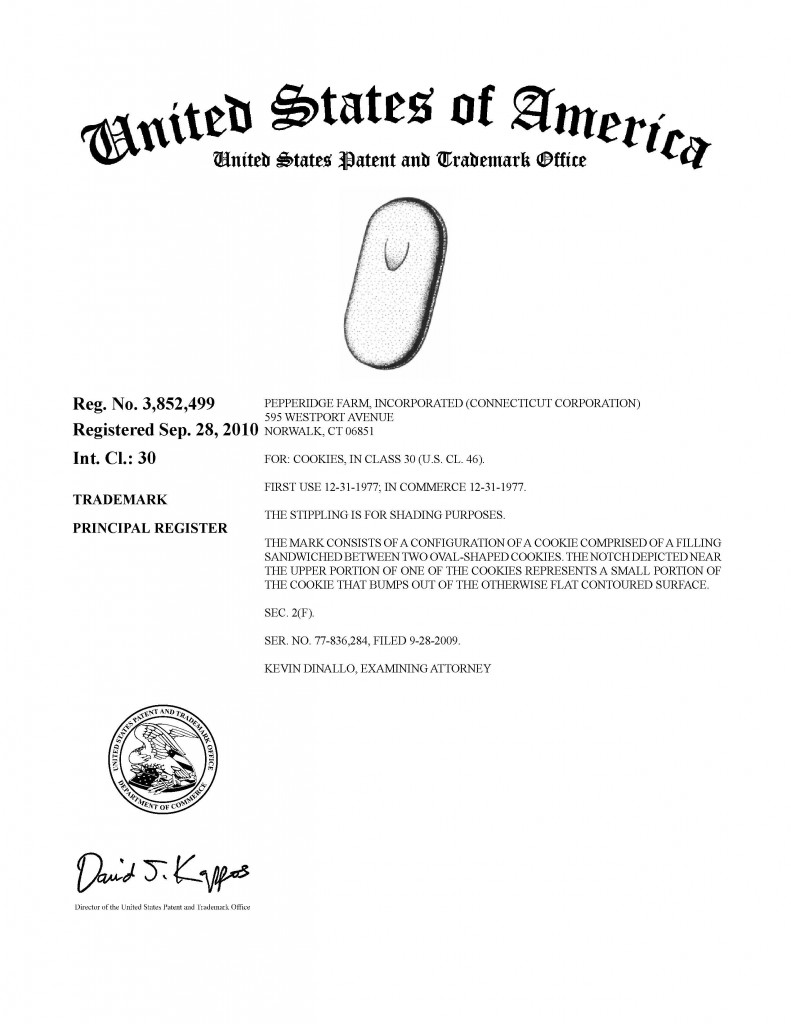

That’s the Way the Cookie Crumbles

On December 2, 2016, Pepperidge Farm sued Trader Joe’s for infringement and dilution of the “famous and unique Milano® cookie configuration trademark. Civil Action 3:15-cv-0174-AWT in the District of Connecticut. While the jury is still out on whether or not a typical cookie-munching consumer can tell the difference between Milanos and Crispy Cookies:

The lesson to be learned from this cookie clash is Pepperidge Farms’ foresight in getting a federal trademark registration on the Milano® cookie configuration:

The registration is “prima facie evidence of the validity of the registered mark and of the registration of the mark, of the registrant’s ownership of the mark, and of the registrant’s exclusive right to use the registered mark in commerce.” 15 USC §1115(a). It is far easier and less expensive to establish rights in a trade dress ex parte before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, than in a contested proceeding in a district court.

While Pepperidge Farms may not have the same success it had against Nabisco back in the 1990’s when it asserted rights in the shape of its Goldfish® crackers (Nabisco, Inc. v. PF Brands, Inc., 191 F.3d 208, 51 U.S.P.Q.2d 1882 (2nd Cir. 1999)), having the registration on the Milano® trade dress gives it a big advantage in its current contest with Trader Joe’s, saving it from having to establish ownership of the trade dress, and allowing it to focus on proving infringement.

No More Pussy-Footing Around: Consider Marks as a Whole in Light of Third-Party Uses

In Jack Wolfskin Aurrustung for Fraussen GmbH & Co. LGAA v. New Millennium Sports, S.L.U, [2014-1789] August 19, 2015, the Federal Circuit affirmed that New Millennium had not abandoned its mark by making changes to its presentation.

The Federal Circuit agreed that the word element of the mark, was “far more distinctive than the lettering in which it is presented” and therefore the change in the style of the lettering did not materially affect the impression created by the word. The Federal Circuit further agree that the addition of claws to the paw prints did not materially altered the mark because the claws are “a very small component” and because “it is common knowledge that an animal’s paws are accompanied by claws.”

Having found that Opposer had not abandoned its mark, the Federal Circuit then turned to the whether applicant’s mark was confusingly similar to Opposer’s mark, as the TTAB had found.

Jack Wolfskin argued that the Board’s decision lacked substantial evidence supporting the similarity of the marks and the number and nature of similar marks in use.

Regarding similarity of the marks, the Federal Circuit noted that marks must be viewed in their entireties, and it is improper to dissect a mark when engaging in this analysis, including when a mark contains both words and a design. Further, when a mark consists of both words and a design, the verbal portion of the mark is the one most likely to indicate the origin of the goods to which it is affixed. The Federal Circuit agreed with applicant that the Board failed to adequately account for the presence of the literal “KELME,” and essentially disregarded the verbal portion of the mark in finding that the paw print designs were substantially similar, failing to consider the marks as a whole.

The Board justified its decision to focus on the paw print elements by stating that companies often use the design portion of a composite mark as shorthand for their brand. The Federal Circuit did not necessarily dispute this, but said that the concept could not be invoked without supporting evidence. This is not to say that the Board cannot, in appropriate circumstances, give greater weight to a design component of a composite mark, but when it places such heavy emphasis on an oft-used design element, it must provide a rational reason for doing so.

Regarding third party usage, the Federal Circuit said that evidence of third-party use bears on the strength or weakness of an opposer’s mark. The weaker an opposer’s mark, the closer an applicant’s mark can come without causing a likelihood of confusion and thereby invading what amounts to its comparatively narrower range of protection. The Federal Circuit determined that the extensive evidence of third-party uses and registrations of paw prints indicates that consumers are not as likely confused by different, albeit similar looking, paw prints, and thus the conclusion that this factor was neutral is not supported by substantial evidence.

Out of the Frying Pan, Into Disclaimer

In In re Louisiana Fish Fry Products, Inc., [2013-1619], (August 14, 2015), the Federal Circuit affirmed the TTAB’s decision affirming the refusal of registration of LOUISIANA FISH FRY PRODUCTS BRING THE TASTE OF LOUISIANA HOME! without a disclaimer of FISH FRY PRODUCTS. The Applicant argued that the term FISH FRY PRODUCTS was not generic, and had acquired secondary meaning during its thirty years of use.

The Federal Circuit found that substantial evidence supported the TTAB’s factual finding that applicant had not established that FISH FRY PRODUCTS had acquired distinctiveness. The Federal Circuit said that for highly descriptive terms such as FISH FRY PRODUCTS the TTAB is within its discretion not to accept evidence of five years’ use as establishing acquired distinctiveness. The Federal Circuit also agreed with the TTAB that evidence of use of LOUISIANA FISH FRY PRODUCTS did not necessarily establish that FISH FRY PRODUCTS had acquired distinctiveness. The Federal Circuit agreed that the evidence did not establish that the specific term at issue, FISH FRY PRODUCTS, had acquired distinctiveness.

Peace, Love, and Lawyers

In Juice Generation, Inc. v, GS Enterprises, LLC, [2014-1853] (July 20, 2015), the Federal Circuit vacated a TTAB decision sustaining GS Enterprises’ opposition to Juice Generation’s application to register PEACE LOVE AND JUICE based upon their PEACE & LOVE marks for restaurant services, including:

Reviewing the Board’s likelihood of confusion determination de novo, the Federal Circuit noted that although Juice Generation introduced evidence of a fair number of third-party uses of marks containing “peace” and “love” followed by a third, product-identifying term, the Board discounted the evidence because there were no “specifics regarding the extent of sales or promotional efforts surrounding the third-party marks and, thus, what impact, if any, these uses have made in the minds of the purchasing public.” The Federal Circuit found that the Board’s treatment of the evidence of third-party marks did not adequately account for the apparent force of that evidence. While the specifics as to the extent and impact of use not have been proven, the Federal Circuit found the evidence “powerful on its face”. The Federal Circuit said that the Board overlooked the fact that regardless of the extend of use, extensive evidence of third-party use and registrations indicates that the phrase PEACE & LOVE carries a suggestive or descriptive connotation in the food service industry, and is weak for that reason.

The Federal Circuit also found that the Board improperly failed to consider the marks as a whole when it declared that “PEACE LOVE” is the “dominant” portion of applicant’s marks, and compared only that portion to GS’s “PEACE & LOVE” marks. The Federal Circuit said that this analysis did not display any consideration of how the three word phrase in Juice Generation’s mark might convey a distinct meaning—including by having different connotations in consumers’ minds—from the two-word phrase. The Federal Circuit also observed that it was improper to give no significance to the disclaimed term JUICE because the consuming public encountering the mark would be unaware of the disclaimer.

The Board’s decision does not seem out of line with their past practice; perhaps the Federal Circuit is trying to inject more real world considerations into their process because after In B&B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Industries, Inc. the Board’s decisions may have greater impact on the real world.

Actually Providing Services Key to Service Mark Use

In Couture v. Playdom, Inc., [2014-1480] (Fed. Cir. March 2, 2015), the Federal Circuit affirmed the cancellation of Couture’s federal registration on PLAYDOM because while on the May 30, 2008. filing date Couture had advertised the services, he did not actually perform the services until 2010 long after the Registration issued on January 13, 2009. Although the Federal Circuit had not previously addressed the question, it found that “[o]n its face, the statute is clear.” 15 U.S.C. § 1051(a)(1) required use in commerce, and 15 U.S.C. §1127 defined use as rendering the services in commerce. The Federal Circuit noted that the Second, Fourth, and Eighth have also indicated that actually performing the services, as opposed to merely advertising them, is required for a use-based service mark application.

.