In In re I.AM.SYMBOLIC, LLC, [2016-1507, 2016-1508, 2016-1509] (August 8, 2017), the Federal Circuit affirmed the decision of the TTAB affirming the Trademark Examiner’s refusal of registration of the mark I AM on grounds of likelihood of confusion.

After initial refusals of registration of the I AM mark in Classes 3, 9, and 14, I AM SYMBOLIC amended its description of goods to include the limitation that the goods were “associated with William Adams, professionally known as ‘will.i.am.’” The Examiner maintained the refusal, and the Board affirmed, noting “we do not see the language as imposing a meaningful limitation on [Symbolic’s] goods in any fashion, most especially with respect to either trade channels or class of purchasers.

Before the Federal Circuit I AM SYMBOLIC argued Symbolic argues that the Board erred in its likelihood of confusion analysis by: (1) holding that the will.i.am restriction is “precatory” and “meaningless” and therefore not considering it in analyzing certain DuPont factors; (2) ignoring third-party use and the peaceful coexistence on the primary and supplemental registers and in the marketplace of other I AM marks; and (3) finding a likelihood of reverse confusion.

Regarding the will.i.am restriction, the Federal Circuit said I AM SYMBOLIC failed to show that the Board erred in finding that the restriction does not impose a meaningful limitation in this case for purposes of likelihood of confusion analysis. Under a proper analysis of the du Pont factors, the goods are identical or related and the channels of trade are identical, and thus there is a likelihood of confusion.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board that the purported restriction does not (1) limit the goods “with respect to either trade channels or class of purchasers”; (2) “alter the nature of the goods identified”; or (3) “represent that the goods will be marketed in any particular, limited way, through any particular, limited trade channels, or to any particular class of customers.” In the absence of meaningful limitations in either the application or the cited registrations, the Board properly presumed that the goods travel through all usual channels of trade and are offered to all normal potential purchasers.

Regarding other I AM marks, the Federal Circuit rejected the argument that because applicant’s class 25 registration had co-existed with the cited class 3, 9 and 14 registrations that there was no likelihood of confusion. The ownership of a registraiton on one class does not give a right to register the same]mark on an expanded line of goods, where the use of the mark covered by such registration would lead to a likelihood of confusion, mistake or deception.

With respect to third party marks, the Federal Circuit found that I AM SYMBOLIC did not show sufficient third party use to raise an issue in classes 3 and 9, and in class 14, the Federal Circuit found that the strength of the similarity of the marks and of the goods was sufficient to any error in

failing to specifically analyze the potential weakness of registrants’ marks based on limited third-party use.

Regarding the alleged finding of “reverse confusion,” the Federal Circuit attributed the Board’s comments to a response to the arguments about the fame of the applicant being insufficient, not to an express finding of reverse confusion.

Overall, the Federal Circuit found sufficient evidence to support the Board’s finding I.AM confusingly similar to the cited registrations, and sustain the refusal of registered.

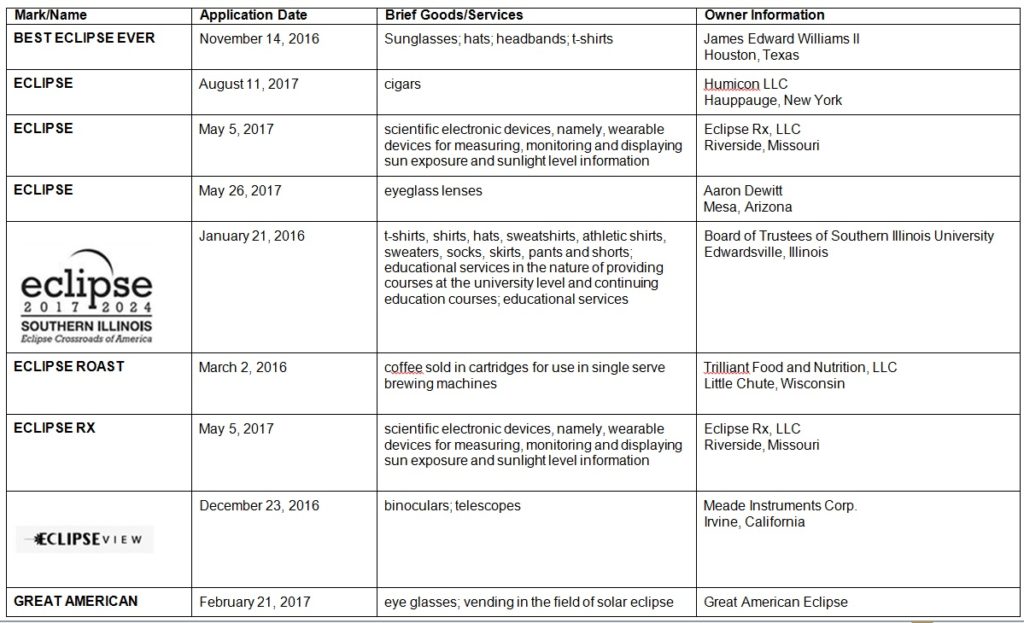

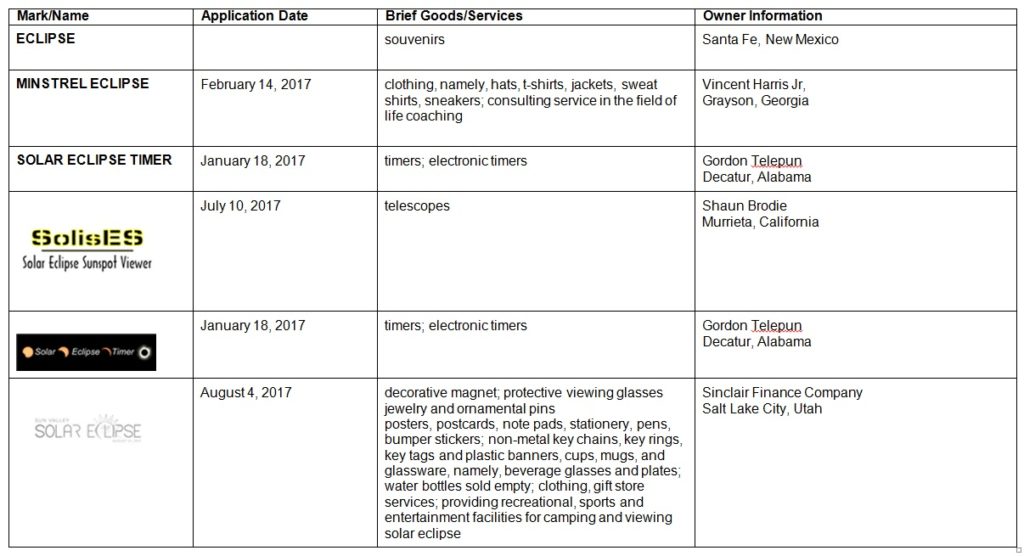

The most questionable trademark strategy is that of Sinclair Finance Group, application on SUN VALLEY SOLAR ECLIPSE AUGUST 21, 2017 was filed on August 4, 2017.

The most questionable trademark strategy is that of Sinclair Finance Group, application on SUN VALLEY SOLAR ECLIPSE AUGUST 21, 2017 was filed on August 4, 2017.