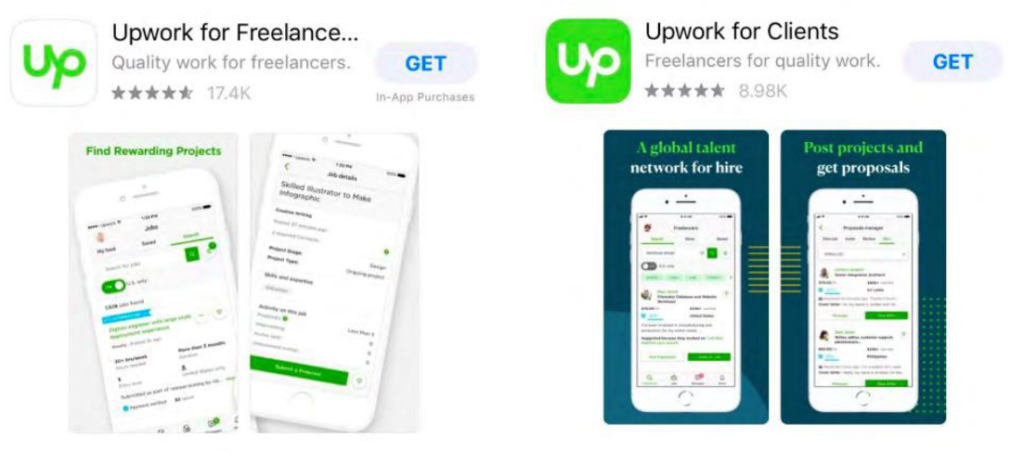

In Freelancer International Pty Ltd v. Upwork Global, Inc., the Ninth Circuit recently (June 22, 2021) affirmed the Northern District of California’s denial of a preliminary injunction against Upworks’s use of Freelancer’s registered trademark FREELANCER in the name of its app “Upwork for Freelancers.” Upwork had apps for it clients, called Upwork for Clients and an corresponding app for the freelancers it placed called Upwork for Freelancers:

Once downloaded to a device, Upwork’s “Upwork for Freelancers” provides its display name, listed beneath the app’s “Up” logo icon, as “Freelancer” on iOS devices and as “Freelancer-Upwork” on Android devices — This is what Freelancer objected to.

The district court found that Freelancer lacked the required likelihood of success. Upwork argued that its use of “freelancer” was a fair use under 15 USC 1115(b)(4). The district court said that the fair use defense is applicable in instances where defendants’ alleged infringing use of plaintiff’s mark “is a use, otherwise than as a mark . . . of a term or device which is descriptive of and used fairly and in good faith only to describe the goods or services of such party, or their geographic origin.” The court noted that defendants submitted evidence showing (1) defendants use the word “freelancer” to describe their users and (2) the word “freelancer” is well-known and defined as “someone who is not permanently employed by a particular company, but sells their services to more than one company.” The court found that plaintiffs did not offer a persuasive refutation of defendants’ fair use argument, dismissing the fair use defense as inapplicable because plaintiffs do not challenge defendants’ use of the word “Freelancer” where it is not used “as a mark.”

The court discussed and rejected Freelancer’s arguments, finding that the instances in which Upwork allegedly uses “freelancer” as a mark are proper and descriptive uses of a common word distinguishing Upwork’s freelancer app from its client app. The Court was not persuaded that bold font and a capital letter are sufficient to show defendants use “Freelancer” as a mark versus a descriptive term – especially when Upwork’s distinctive lime green logo or coloring is placed directly alongside the various notifications. The Court noted that Upwork did not list the word “Freelancer” among its own publicly listed trademarks, nor did Upwork implement a stylized font or “TM” symbol when using the word “Freelancer.”

Based on the current record, the court found that Upwork does not use “freelancer” as a mark, rather, Upwork’s used the word in good faith to describe its users, and thus the court agreed that the defendants’ use of the word “freelancer” satisfies the requirements of fair use under 15 U.S.C. § 1115(b)(4).

The 9th Circuit concluded that the district court did not abuse its discretion by concluding that Freelancer could not carry its burden to show likely success on the merits.

The case provides some helpful guidelines to companies trying to use a registered mark descriptively: Avoid presenting the mark in a stylized font and avoid identifying the term with a TM. Capitalization and bolding are not enough to change this, at least where the user’s trademark is also prominently displayed. The case also provides a helpful reminder to brand owners: The more descriptive your mark, the more likely a third party use of the term will be found to be a descriptive use.