An interesting suit was filed on October 27 in the Norther District of Ohio by the Guardians Roller Derby team against the Cleveland Guardians Baseball Company f/k/a the Cleveland Indians. The Cleveland Indians after 105 years decided to change their name the Cleveland Guardians, and if the Complaint is to be believed, did so with full knowledge of another Cleveland sports team already using the name, the Cleveland Guardians roller derby team.

As the Complaint (Para. 20) alleges,”it is inconceivable that an organization worth more than $1B and estimated to have annual revenues of $290M+ would not at least have performed a Google search for “Cleveland Guardians” before settling on the name.”

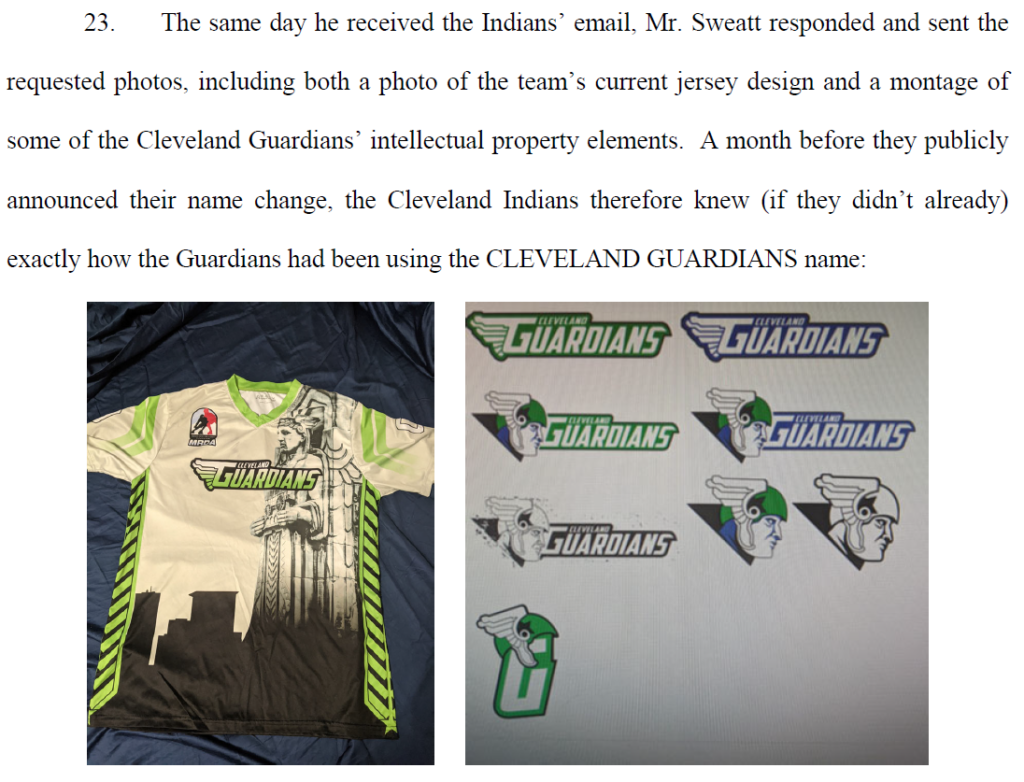

The Complaint lays out the history of events:

While the strategy of filing in a remote jurisdiction to hide interest in a mark from prying eyes is a common one, employed by many large companies, including Apple, and not as sinister as the Complaint implies, the Indians conduct in the face of a party with superior rights seems rather cavalier — wait, no, that’s a different Cleveland team.

The Complaint alleged that “Two sports teams in the same city cannot have identical names. Major League Baseball would never permit “Chicago Cubs” lacrosse or “New York Yankees” rugby teams to operate alongside its storied baseball clubs and rightly so. Confusion would otherwise result. Imagine seeing a “New York Yankees” shirt for sale and buying it. Which team did you just support?” There are certainly problems in such a scenario, although it worked for years in St. Louis, which had both a Cardinals baseball team and a Cardinals football team. This was a special circumstance where similarly named teams, with long histories, found themselves in the same city.

No doubt this will be settled, and there will plenty of branded baseball merchandise to buy in the Forest City, and the city’s newly renamed roller derby team will be the best funded roller derby team in the country. The lesson, if there is one, is to not fall in love with a new name until after it is properly cleared.