In re Forney Industries, Inc., [2019-1073] (April 8, 2020), the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded the TTAB’s affirmance of the refusal to register Forney’s proposed mark on grounds that the proposed mark is of a type that can never be inherently distinctive.

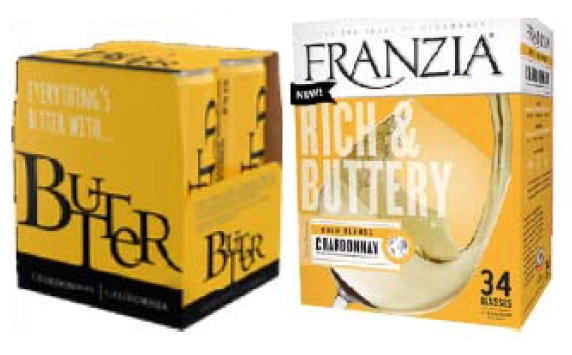

On May 1, 2014, Forney filed Trademark Application No. 86/269,096 for its proposed mark for packaging for various welding and machining goods based on use in commerce under Section 1(a) of the Lanham Act.

The Examiner refused registration under Sections 1, 2, and 45 of the Lanham Act because the mark was not inherently distinctive. The examining attorney noted that such marks are registrable only on the Supplemental Register or on the Principal Register with sufficient proof of acquired distinctiveness.

Forney appealed this decision to the Board, arguing that its proposed mark should be treated as product packaging claiming multiple colors. According to Forney, its proposed mark is product packaging trade dress that may be inherently distinctive and, therefore, registrable without proof of acquired distinctiveness, but the Board affirmed the examining attorney’s refusal to register, treating the proposed mark as a color mark consisting of multiple colors applied to product packaging. The Board found that, when assessing marks consisting of color, there is no distinction between colors applied to products and colors applied to product packaging. The Board found no legal distinction between a mark consisting of a single color and one, such as Forney’s, consisting of multiple colors with-out additional elements, e.g., shapes or designs.

The Federal Circuit found that the Board erred in two ways: (1) by concluding that a color-based trade dress mark can never be inherently distinctive without differentiating between product design and product packaging marks; and (2) by concluding (presumably in the alternative) that product packaging marks that employ color cannot be inherently distinctive in the absence of an association with a well-defined peripheral shape or border.

The Federal Circuit held that color marks can be inherently distinctive when used on product packaging, depending upon the character of the color design. As the Supreme Court made clear, inherent distinctiveness turns on whether consumers would be predisposed to equate the color feature with the source. While it is true that color is usually perceived as ornamentation a distinct color-based product packaging mark can indicate the source of the goods to a consumer, and, therefore, can be inherently distinctive.

The Federal Circuit found that as a source indicator, Forney’s multi-color product packaging mark is more akin to the mark at issue in Two Pesos than those at issue in Qualitex and Wal-mart. The Federal Circuit said it falls firmly within the category of marks the Court described as potential source identifiers. Supreme Court precedent simply does not support the Board’s conclusion that a product packaging mark based on color can never be inherently distinctive. The Federal Circuit noted that it was not the only court to conclude that color marks on product packaging can be inherently distinctive.

The Federal Circuit concluded that Forney’s proposed mark comprises the color red fading into yellow in a gradient, with a horizontal black bar at the end of the gradient. It is possible that such a mark can be perceived by consumers to suggest the source of the goods in that type of packaging. Accordingly, rather than blanketly holding that colors alone cannot be inherently distinctive, the Board should have considered whether Forney’s mark satisfies the Federal Circuit’s criteria for inherent distinctiveness.

On the alternate grounds, the Federal Circuit said that without explaining why it was doing so, the Board found that a color may only be inherently distinctive when used in conjunction with a distinctive peripheral shape or border. The Federal Circuit said that “nothing in the case law mandates such a rule.”

In determining the inherent distinctiveness of trade dress, the question to be answered is whether the trade dress makes such an impression on consumers that they will assume the trade dress is associated with a particular source. To assess that question, the Board must look to the following factors: (1) whether the trade dress is a “common” basic shape or design; (2) whether it is unique or unusual in the particular field; (3) whether it is a mere refinement of a commonly-adopted and well-known form of ornamentation for a particular class of goods viewed by the public as a dress or ornamentation for the goods; or, inapplicable here, (4) whether it is capable of creating a commercial impression distinct from the accompanying words. Id. (collecting cases). These factors are all different ways to determine whether it is reasonable to assume that customers in the relevant market will perceive the trade dress as an indicator of origin.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the Board erred in stating that a multi-color product packaging mark can never be inherently distinctive. To the extent the Board’s decision suggests that a multi-color mark must be associated with a specific peripheral shape in order to be inherently distinctive, that too, was error. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded for the Board to consider, whether, for the uses proposed, Forney’s proposed mark is inherently distinctive under the Seabrook factors, considering the impression created by an overall view of the elements claimed.