Lucas Film Limited has sued Michael Brown and his Light Saber Academy for trademark infringement, unfair competition, dilution, cybersquatting, state unfair competition, and dilution, arising from Mr. Brown’s running an academy promoting, producing, offering for sale and selling unauthorized “Lightsaber” classes, which purport to teach students how to use “Lightsabers” and/or perform as “Jedi.”

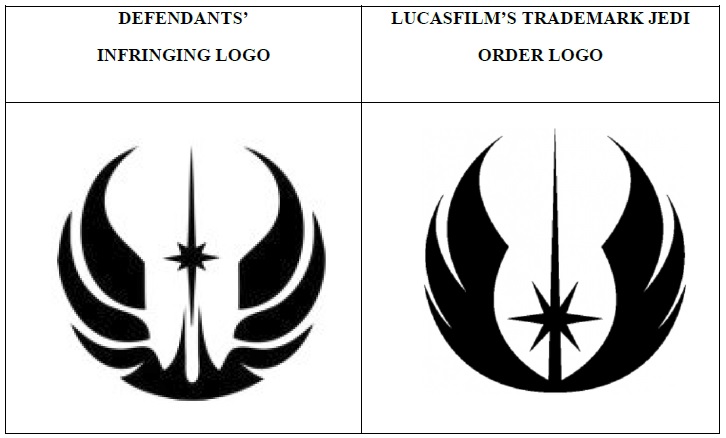

The Academy appears to claim trademark rights in LIGHTSABER ACADEMY, tagging it with a TM, and has adopted a logo that is similar to the Jedi logo created by Lucas Film:

But what should Mr. Brown call his school for teaching the use of lightsabers? Doesn’t he have a right to truthfully describe his services to potential customers? Of course he does. Trademarks only protect against confusion of source. Mr. Brown has the right to describe his activities, and even use the trademark of others in doing so, as long as he does not cause confusion, mistake or deception. Whether crossed that line, Mr. Brown has, is now for the Northern District of California to decide.

Lucas Films v. Brown raises an interesting question of what rights creators retain when their works become part of the cultural commons? There are many instances where an idea introduced by a popular book or movie is developed by third parties, and as long as copyrights are not infringed, and the public is not likely to be confused, those ideas become part of our cultural commons free for all to use. For example, there is a Klingon Language Institute (http://www.kli.org/) to learn Klingon, the language of the fictional Klingon race in Star Trek.

It will be interesting to see what happens, but it’s important to remember the old Klingon proverb: qech wej QaD trademark nIH! (Trademarks don’t protect ideas).