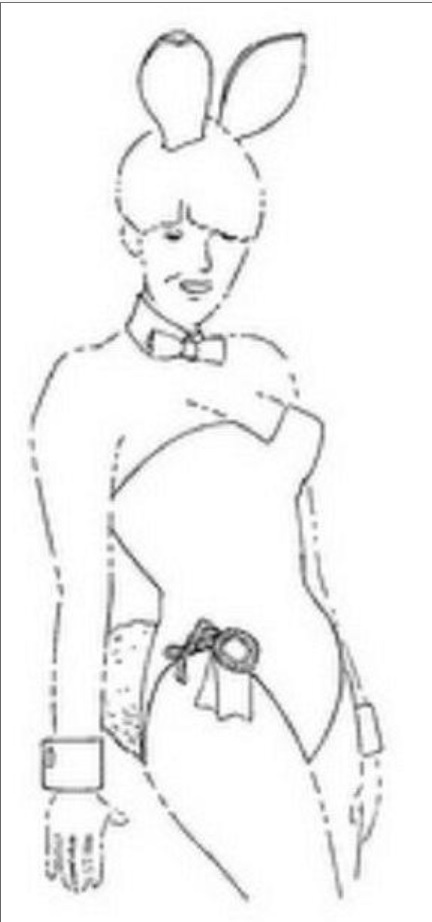

Costumes and uniforms may be distinctive of a business, and thus may function as a trademark or service mark, identifying the business and distinguishing it from other business.

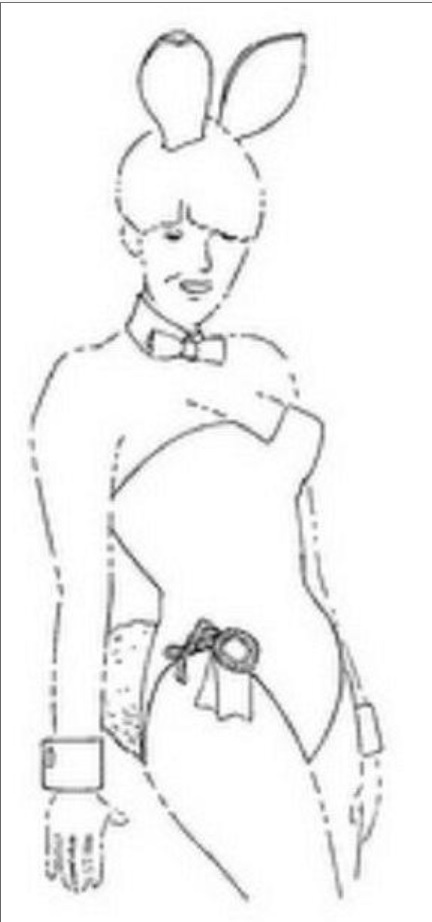

Thus, there are registrations on the uniforms of “entertainers” for entertainment services. Reg. Nos. 3234488, 3319643, 3353308, 3392817, 3848988 and Application Nos. 86690033 and 86731130 protect the three dimensional bunny costume used by Playboy Enterprises.

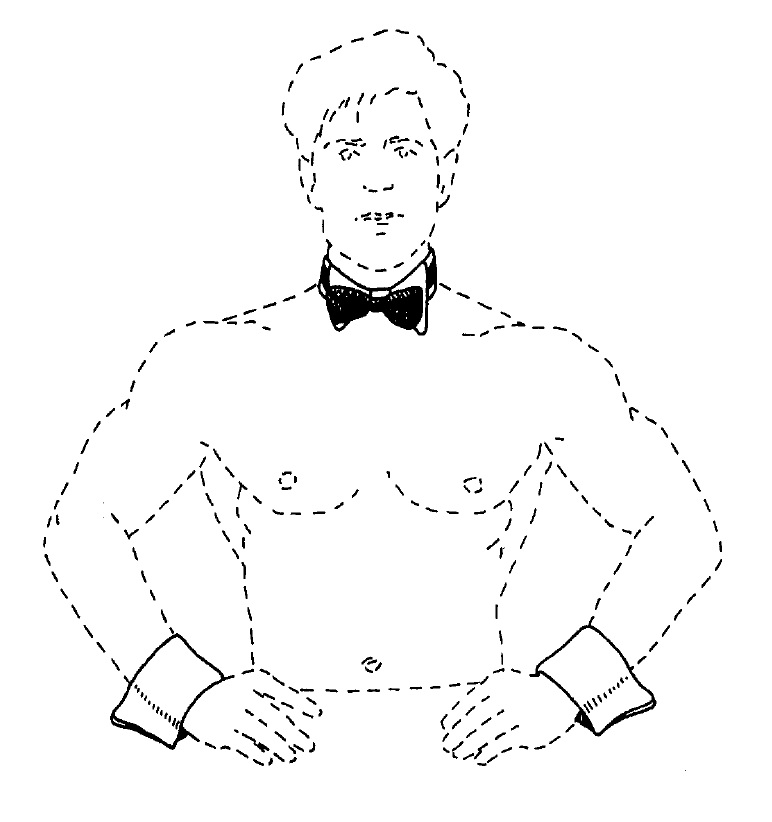

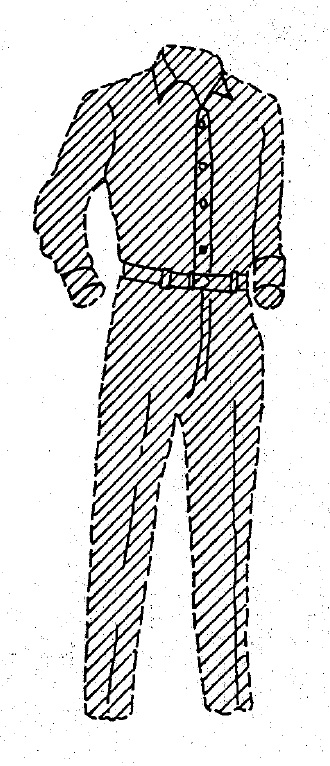

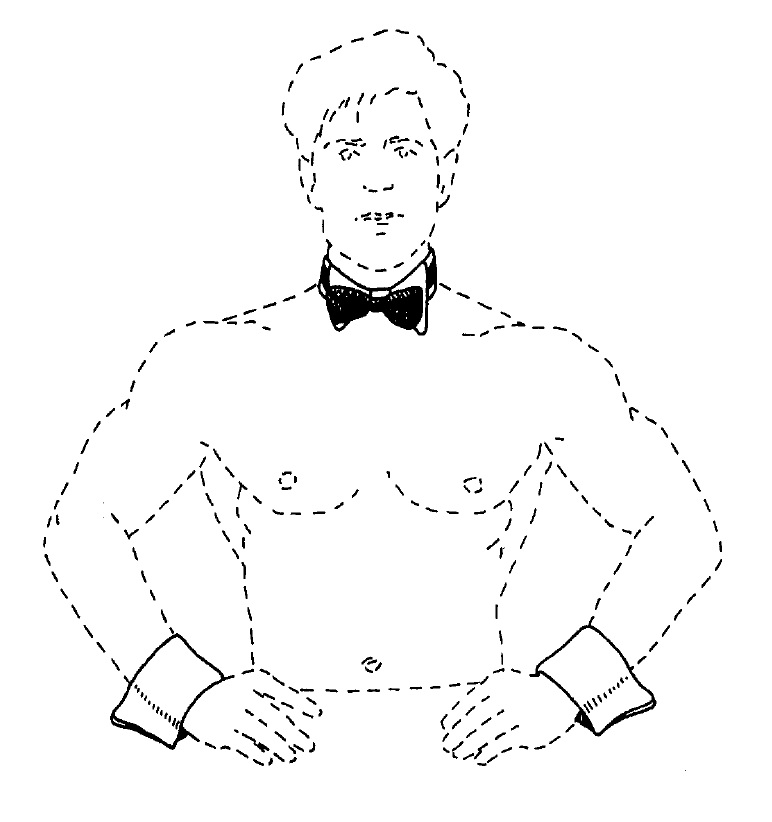

Reg. No. 2694613 protects the “costume” (or lack thereof) of the Chippendales:

There are registrations on the uniforms of food servers for restaurant services. Reg. No. 4058758 protect the server uniforms at the Tilted Kilt:

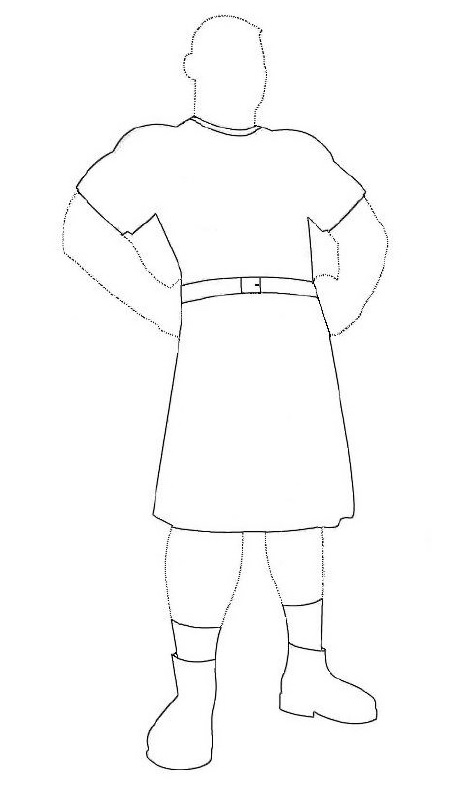

And, to be fair, Reg. No. 4936100 protects a kilt for cleaning and maintenance services by Men in Kilts:

There are registrations on the uniforms of sports teams for entertainment services. Reg. Nos. 4962486 and 4962487 protect the uniforms of the Washington Bullets:

Reg. Nos. 2015037 and 2188043 on the uniforms for the New York Knicks; Reg. No. 2020341 on the uniforms for the Chicago Bulls; Reg. No. 1812445 on the jerseys of the Philadelphia Flyers; Reg. No. 2029421 on the pinstriped uniforms for the New York Yankees.

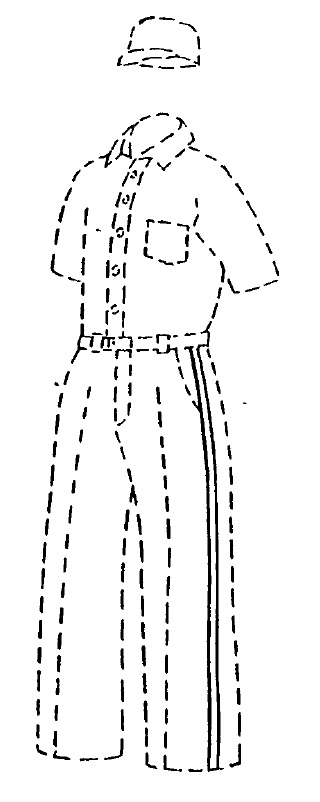

There are registrations on the uniforms of services providers for various other services, such as flight attendants (Reg. No. 3773705 by Korean Airlines):

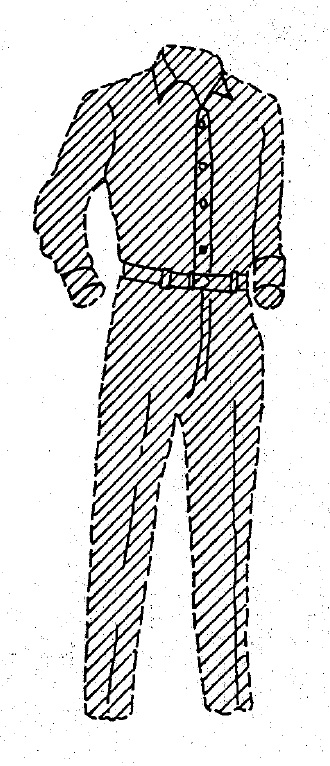

parcel delivery (Reg. No. 2159865 by United Parcel Service):

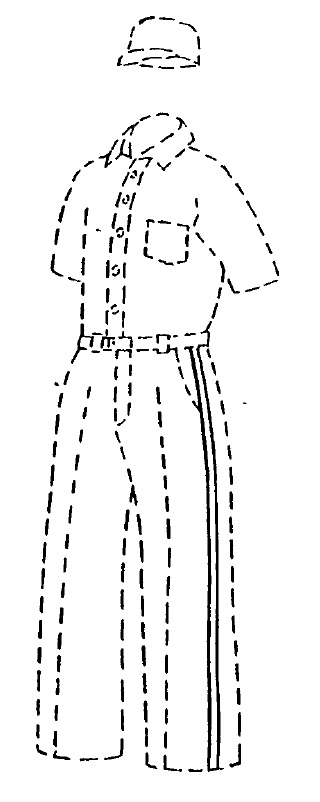

and (Reg. No. 3061549 by U.S. Postal Service):

(the US Postal Services also owns Reg. Nos. 3,061,544, 3,061,545, 3,061,546, and 3,061,547); Cheerleading (Reg. No. 2906113 by Dallas Cowboys):

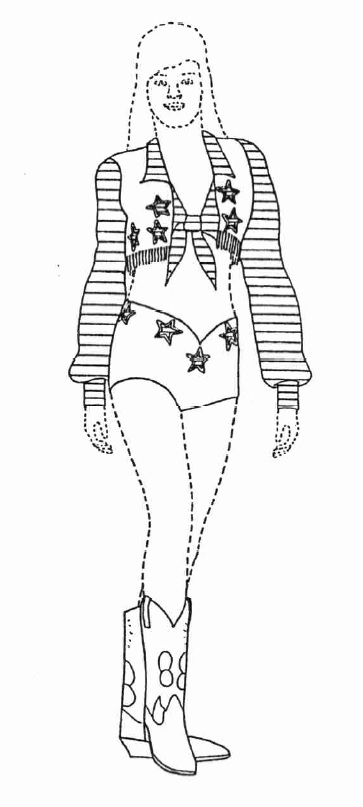

Other examples are Reg. No. 2135563 on a taco costume for restaurant services; Reg. No. 1999006 on uniform for tour guides; Serial No. 87007353 on a duck costume for car wash services; Reg. No. 4986282 on a robot costume for DJ services; Serial No. 86640889 on a blue cheese costume for baseball mascot; Reg. No. 4221509 on a costume for performers; Reg. No 4558197 on a showgirl costume for casino services; Reg. No. 4558198 on a lobster costume for casino services.

While they say that clothes make the man (or woman); they sometimes make the trademark.

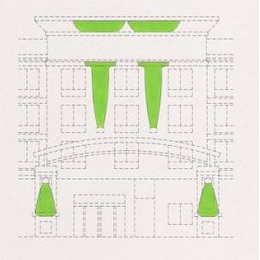

Trade dress is a combination of features that the owner believes makes its product. Diageo identified its trade dress as comprising:

Trade dress is a combination of features that the owner believes makes its product. Diageo identified its trade dress as comprising: