In Matal v, Tam, the Supreme Court affirmed the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in holding that the 15 USC §1052(a)’s prohibition against the registration of disparaging marks was unconstitutional as a violation of the First Amendment, 15 USC §1052(a) provides:

(a) Consists of or comprises immoral, deceptive, or scandalous matter; or matter which may disparage or falsely suggest a connection with persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or bring them into contempt, or disrepute;

While the case before the Supreme Court related to disparaging marks (the same prohibition that caused the Washington Redskins to lose their registrations on REDSKINS), in January in In re Brunetti, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office told the Federal Circuit that:

Although a court could draw constitutionally significant distinctions between these two parts of [§1052(a)] we do not believe, given the breadth of the court’s Tam decision and in view of the totality of the court’s reasoning there, that there is any longer a reasonable basis in this court’s law for treating them differently.

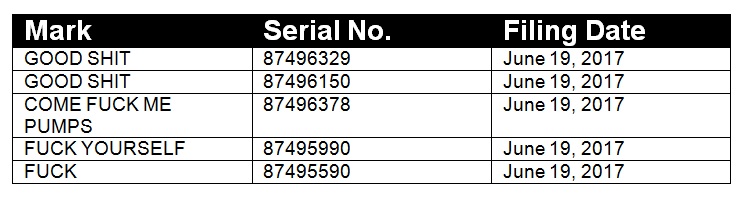

So, its now open season on immoral, scandalous, and disparaging trademarks. It didn’t take long for applicants to take advantage of the decision, with applications being filed later the same day.

These types of filings actually began shortly after the Federal Circuit’s December 22, 2015, decision, and will no doubt increase with the Supreme Court’s decision.