On June 3, 1969, U.S. Reg. No. 870506 issued on the mark MARVEL for COMIC BOOKS AND MAGAZINES, although the mark was first used almost 30 years on August 31, 1939.

Let the Chips Fall Where they May

On May 27, 2025, Mondelez International, Inc. sued Aldi, Inc. for “use of private label product packaging that blatantly copies and trades upon the valuable reputation and goodwill ” of Mondelez. See 25-cv-05905 now pending in the Northern District of Illinois. The Four Count Complaint for Federal Trade Dress Infringement, Federal Trademark Dilution, Unfair Competition, Dilution, provides this comparison between Mondelez’ and Aldi’s products:

Private label (aka store brand) products often copy elements of the national brands packaging, to convey a message of equivalence and to invite comparison, but sometimes the private label can go too far. What the Norther District of Illinois will have to sort out is whether Aldi has gone too far with its packaging.

Mondelez will have to show that Aldi’s packaging infringes Mondelez’ trade dress — that combination of non-functional packaging features that consumers rely upon to find the products they want. Mondelez’ burden may be made more difficult by Aldi’s modus operandi. As reported on foodindustrynetwork.com “Aldi dominates in private-label share for grocery, household, and health and beauty products, which account for more than three-quarters (77.5%) of its total sales, Numerator’s private-label trend tracker shows. Roughly 90% of the items in Aldi’s stores are own brands.” (https://foodindustrynetwork.com/aldi-leads-in-private-label-volume-growth/) In an environment where 90% of the items are Aldi’s brands, is any Aldi customer really confused about what they are getting?

If Aldi’s chose to convey its message of equivalence with different packaging with a written “Compare to” message would Mondelez be any less unhappy? Yes, there are similarities in the packages, but we will have to wait to see whether Mondelez can show that Aldi’s has gone too far.

April 2, 2025

An Award of Defendant’s Profits, Does Not Include Defendant’s Affiliates’ Profits

In Dewberry Group, Inc. f; Dewberry Engineers Inc., — US — (2025), the Supreme Court made the unremarkable decision that an award of a defendant’s profits under 15 USC 1117(a), is limited to the named defendant, and not to unnamed affiliates of the defendant.

The district court had held that considering the actual defendant and its affiliates together would prevent the “unjust enrichment” that the Act was meant to target and totaled the affiliates’ profits from the years Dewberry Group infringed, resulting in An award of nearly $43 million. Reiterating the “‘economic reality’ of Dewberry Group’s relationship

with its affiliates,” the Fourth Circuit approved the treatment of all the companies “as a single

corporate entity.” holding Dewberry Group to account for its use of infringing materials to generate corporate profits.

Noting that the Lanham Act authorizes the recovery of the defendant’s profits, the Supreme Court said that in the absence of a specific definition, the word “defendant” bears its usual legal meaning: “the party against whom relief or recovery is sought in an action or suit,” i.e. the Dewberry Group. The Court observed that the plaintiff chose not to add the Group’s property-owning affiliates as defendants, and thus the affiliates’ profits are not the (statutorily

disgorgable) “defendant’s profits” as ordinarily understood.

The Supreme Court said that background corporate law principles do not change the result, for it is long settled as a matter of American corporate law that separately incorporated organizations are separate legal units with distinct legal rights and obligations — even if they are affiliated. Noting that Dewberry Engineers admitted it never tried to make the showing needed for veil-piercing, the Court said that the need to respect corporate formalities remains..

Plaintiff attempted to support the award by invoking a later sentence in Section 1117(a): “If the court shall find that the amount of the recovery based on profits is either inadequate or excessive[,] the court may in its discretion enter judgment for such sum as the court shall find to be just, according to the circumstances.” Plaintiff argued that a court can

consider “as relevant evidence” the profits of related entities— for example, to see if the defendant diverted some of its earnings to an affiliate’s books. But the Supreme Court said that this is not what was done:

The District Court did not rely on the just-sum provision, or suggest that it was departing up from Dewberry Group’s reported profits to reflect the company’s true gain. There was no two-step process for deciding on the award, but only a single step: the calculation of the “defendant’s profits.”

The Court added that that treatment, by its terms, disregards “corporate formalities”—and likewise the “principle[] of corporate separateness.”

The Supreme Court thus vacated the judgment of the Fourth Circuit, and remanded the case for further proceedings, expressly leaving open the question of the effect of the “just sum” provision when properly applied, and whether veil-piercing is an available option on remand,

CoorsTek in the Pink as CeramTec’s Trademark Registrations Get Pink Slips for Functionality

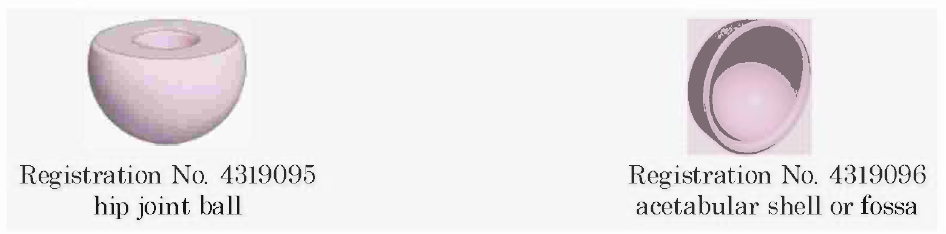

In CeramTec GmbH v. CoorsTek BIoceramics LLC, [2023-1502[(January 3, 2025), the Federal Circuit affirmed the TTAB’s cancellation of CeramTec’s trademark registrations on the pink color of ceramic hip components.

CeramTec manufactures artificial hip components used to replace damaged bone and cartilage in hip replacement procedures. The hip components are made from a zirconia toughened alumina (“ZTA”) ceramic originally developed for use in cutting tools. The ZTA ceramic contains, among other things, chromium oxide (chromia). The chemical composition of CeramTec’s products was the subject of CeramTec’s U.S. Patent 5,830,816 until January 2013, when the patent expired. The ’816 patent’s specification and prosecution history discuss how adding chromia enables the claimed composition to obtain unprecedented levels of hardness. Increased hardness levels enable the ZTA hip component to maintain its shape and resist deformation. The range of chromia claimed in the ’816 patent can produce ZTA ceramics in a variety of colors, such as pink, red, purple, yellow, black, gray, and white. CeramTec’s components contain chromia at a 0.33 weight percentage, which makes it pink.

A year before the expiration of its patent, CeramTec applied for two trademarks claiming protection for the color pink used in ceramic hip components, and two registrations issued on the Supplemental Register in April 2013:

:.

CoorsTek manufactures two ZTA ceramic materials for hip implants: (1) CeraSurf-p, which contains chromia, rendering it pink, and (2) CeraSurf-w, which does not contain chromia,

rendering it white. On March 3, 2014, CoorsTek filed a lawsuit in the District of Colorado and a cancellation petition with the Board, both seeking to cancel CeramTec’s trademarks on

the ground that the color pink claimed was functional.

At the Board, CeramTec argued that although it had once believed that adding chromia

provided material benefits to ZTA ceramics [upon the expiration of their patent] they discovered this belief was mistaken and has since been disproven. The Board nonetheless found in favor of CoorsTek and concluded that the color pink was functional as it relates to ceramic hip components. In doing so, the Board rejected CeramTec’s unclean hands defense, in which CeramTec argued that CoorsTek should be precluded from petitioning to cancel its trademarks on functionality grounds because CoorsTek had previously contended that chromia provided no material benefits to ZTA ceramics.

On appeal, CeramTec raised two main arguments: (1) that the Board’s finding that its trademarks are functional was infected by legal error and unsupported by substantial

evidence, and (2) that the Board erred by categorically precluding the defense of unclean hands in cancellation proceedings involving functionality.

The Federal Circuit noted that the Board analyzed the functionality of CeramTec’s trademarks in part under the four factors set out in Morton–Norwich:

(1) the existence of a utility patent disclosing the utilitarian advantages of the design;

(2) advertising materials in which the originator of the design touts the design’s utilitarian

advantages;

(3) the availability to competitors of functionally equivalent designs; and

(4) facts indicating that the design results in a comparatively simple or cheap method of

manufacturing the product.

Under the first Morton-Norwich factor, the Federal Circuit noted that the Board considered the claims, specification, and prosecution history of the ’816 patent to disclose the “functional

benefits of chromia with respect to the toughness, hardness, stability and suppression of brittleness of the ZTA ceramic.” The Board also considered CeramTec’s other patents and applications. Finally, the Board considered CeramTec’s concessions that the addition of

chromia causes ZTA ceramics to become pink and that CeramTec’s products practice at least one claim of the ’816 patent.

CeramTec contended that it was error for the Board to find that the patents disclose that chromia provides utilitarian advantages to ZTA ceramics in addition to increasing hardness, but CeramTec’s admission that it did increase hardness was enough for the Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit als rejected the assertion that the Board misapplied TrafFix because its patents do not explicitly disclose material benefits for pink ZTA ceramics and do not discuss hip components, only cutting tools, noting nowhere does TrafFix hold that for a patent to be evidence of a claimed feature’s functionality, the patent must explicitly disclose that the claimed feature is functional. Nor does TrafFix state that for a trademark to be subject

to a TrafFix analysis it must be used for the goods described in the patent.

Under the second Morton-Norwich factor the Board considered promotional and technical literature, as well as submissions made to the FDA, in which CeramTec stated that chromia provides various functional benefits to ZTA ceramics. CeramTec did not challege the second factor.

Under the third Morton-Norwich factor the Board recognized, there was no “probative

evidence” that different-colored ceramic hip components were “equivalent in desired ceramic mechanical properties to those of CeramTec’s products. The Federal Circuit agreed, noting that for the third factor to weigh in favor of nonfunctionality, there must be evidence of actual or potential alternative designs “that work equally well” to the trademarked design. CeramTec argued that statements by CoorsTek about its white ceramic components and the’816 patent’s disclosure of ZTA ceramics in a variety of colors in addition to pink showed non-functionality, but the Federal Circuit did not find the evidence undisputeddly provide that CoorsTek’s white ceramic was better than CeramTec’s products. The Federal Circuit found that CeramTec’s arguments amount to a disagreement with the weight the Board assigned to the evidence, which it saw no reason to disturb.

Finally, under the fourth Morton-Norwich factor, the Board found this factor factor—whether the design results in a comparatively simple or cheap method of manufacturing the product—to be neutral. CeramTek argued that the Board overlooked undisputed evidence, but the Federal Circuit found that CeramTec mischaracterized the evidence as undisputed, and in light of the conflicting evidence, the Board reasonably found the factor to not weigh for or

against functionality.

On the issue of unclean hands, CeramTec argued to the Board that CoorsTek should be precluded from asserting that CeramTec’s trademarks are functional because CoorsTek had long expressed the opposite: that chromia provides no material benefits for ZTA ceramics. The Board disagreed, holding that the unclean hands defense is unavailable in Board functionality proceedings in view of the prevailing public interest in removing registrations of functional marks from the register and finding CeramTec’s unclean hands defense inapplicable.

The Federal Circuit agreed that the Board spoke too strongly by suggesting that the unclean hands defense was categorically unavailable in functionality proceedings, noting that the Board’s rules explicitly provide that the registrant in cancellation proceedings before the Board, may include the affirmative defense of unclean hands. However, the Federal Circuit said that it was not clear that the Board intended to announce a broad policy, as its conclusion is preceded by reference to its “discretion,” which is generally exercised case-by-case, and the Board did not designate its decision as precedential. If, however, the Board intended to bar an unclean hands defense from all functionality proceedings, the Federal Circuit said that would be error, but any such error was harmless in the present case because the Board adequately considered whether the unclean hands defense was available in this case, as illustrated by its statement that it was exercising its discretion in view of the “strong public policy interest in cancelling ineligible marks.

.

.

,

Rebranding

There are several reasons why a business might need to rebrand a product — to resolve a dispute over the brand; to continue after the termination or expiration of a license; or to refresh (or rehabilitate) the product’s image. Whatever the reason, rebranding requires careful planning and diligent execution.

- Select a new brand. Define the unique selling proposition and core brand values. Brainstorm and generate brand name ideas. Shortlist brand name candidates, focusing on those that are easy to pronounce, spell, and remember. Research meanings of the candidate brands. If you plan to sell internationally, check for any potential issues in other languages or cultures. A name that’s great in one country might have unintended meanings in another. Screen for availability as domain names (for your website), trademarks (to protect intellectual property), and social media handles. Screen the candidates for legal availability. Test the remaining candidates with the target audience. Make your selection(s).

- Develop the new brand. Revise the logo, color scheme, typography, and graphic elements. Create brand guidelines defining the rules for using brand elements to ensure consistency across all channels. Create a brand story with a compelling narrative that reflects the new brand identity and resonates with the target audience.

- Refresh the product and packaging. Consider changes in product features, packaging, or benefits. Update the design to reflect the new brand identity, attract the target audience, and ensure consistency.

- Protect the new brand, product, and packaging. File trademark applications on the new brand, pursue appropriate trademark, patent, and copyright applications on the product, packaging, and marketing materials.

- Update company documentation: Ensure that internal documents (e.g., contracts, presentations) reflect the new brand.

- Update Digital Presence & Online Assets. Update website and social media profiles, ensuring the new brand is reflected across digital platforms. Revise SEO and content strategy, optimizing the website and digital content to align with the new brand and improve search rankings. Ensure consistent messaging by updating content on blogs, social media, email templates, and digital ads to reflect the new brand. Update any e-commerce platforms, including product listings, descriptions, and images to match the new brand. Revise frequently asked questions and other support documents to match the new product identity.

- Create new advertising. Develop new ads, brochures, and promotional content reflecting the new branding. Organize product relaunch events, online webinars, or media outreach. Collaborate with influencers and media.

- Communicate with existing customers. Send out personalized communication (e.g., email or newsletters) informing customers about the rebrand. Ensure that brochures, product manuals, and customer support documents reflect the new brand. Address potential concerns about product quality or customer service during the transition.

- Address legal and compliance considerations. Revise any licensing, distribution, or partnership agreements to reflect the rebranded product. Verify that all new packaging, advertising, and product claims comply with industry regulations and guidelines.

Rebranding is a complex process that requires careful planning, collaboration, and a focus on consistency across all platforms. A well-executed rebrand can rejuvenate a product, attract new customers, and increase market share.

More for Less

Effective January 18, 2025, the USPTO filing fees for trademark applications are going up, as illustrated on this chart:

| Until January 17, 2025 | After January 17, 2025 | ||

| Use-based application in one class using standard descriptions of goods and services | $250 | $350 | 40% increase |

| Use-based application in one class, using freeform descriptions of goods and services | $350 | $550 | 57.1% increase |

| Intent-to-use application in one class using standard descriptions of goods and services + Statement of Use* | $250 + $100 | $350 + $150 | 42.9% increase |

| Intent-to-use application in one class, using freeform descriptions of goods and services + Statement of Use* | $350 + $100 | $550 + $150 | 55.6% increase |

In addition, there is a new $100 surcharge per class if any of the twenty “Requirements for a base application,” as provided in 37 CFR § 2.22(1) through (20) is omitted, and an additional fee of $200 for each additional group of 1,000 characters in the free-form text box beyond the first 1,000 characters. Thus a mistake or omission can bump the fees for a new single application to $450, and a lengthy description of goods and services adds at least another $200.

One way to minimize government filing fees are to make sure all of the requirements for a base application are met. This may be more difficult than it sounds, because it includes providing a description of the mark, describing all colors in the mark and their locations; providing an English translation of any non-English wording, and providing a transliteration of any non-Latin characters, compliance with which is at least somewhat subjective.

Another way to minimize government filing fees is to select the descriptions of goods and services from the Trademark ID Manual (TMNG-IDM). The ID Manual is often lacking, particularly with respect to modern goods and services. This can be managed with some advance planning – requesting that your goods or services be added to the ID Manual. This is easily done by emailing the name of requester, the email address of the requester, and the proposed identification (no more than 25 words) to tmidsuggest@uspto.gov. No more than three proposals should be submitted in a single email, the proposal(s) should be of use to other applicants (and not just the submitter), and proposal should not be for a description that has been rejected by an Examiner.

A final way to minimize government filing fees is to file separate applications for classes using descriptions from the Trademark ID Manual, and classes needed a freeform description of goods and services.

The fees for maintaining issued registrations are also increasing:

| Until January 17, 2025 | After January 17, 2025 | ||

| Section 8 Affidavit of Use (between the 5th and 6th Anniversary of registration) per class | $225 | $325 | 44.4% increase |

| Combined Section 8 & 15 Affidavits of Use (between the 5th and 6th Anniversary of registration) per class | $225 + $200 | $325 + 250 | 28.1% increase |

| Section 8 Affidavit and Section 9 Renewal per class | $225 + $300 | $325 + $325 | 23.8% increase |

Avoiding Trademark Scams

There is a surprisingly large industry that profits by scamming trademark owners by sending official-looking invoices that mention the recipient’s trademarks, and hoping that the recipient will be fooled into paying it.

How do you avoid getting scammed — often for several thousand dollars? Ask your trusted trademark counsel about any suspicious trademark invoice. What makes a trademark invoice suspicious? First and foremost, did it come from your trusted trademark counsel? Here as some other things to look for:

- Is the return address a post office box?

- Is the return address from a city remote from the USPTO?

- Is the return address from a foreign country?

- Does the document refer to an “offer” or “solicitation”?

- Does the document refer to “listing” your in a directory or publication?

- Is there a portion to clip and return?

- Does the URL or email address end in .org or.biz or another unusual domain?

Be careful and only deal with your trusted trademark counsel.

The USPTO Cannot Sleep at Night Unless it Knows Where YOU Sleep at Night

On February 13, 2024, the Federal Circuit affirmed the USPTO’s refusal to register the mark CHESTEK LEGAL for failure to comply with the domicile address requirement of 37 C.F.R. §§ 2.32(a)(2) and 2.189.

37 C.F.R. §2.32(a)(2) requires that a trademark application include “[t]he name, domicile address, and email address of each applicant.” While 37 C.F.R. § 2.189 requires that “An applicant or registrant must provide and keep current the address of its domicile, as defined in § 2.2(o) [The term domicile as used in this part means the permanent legal place of residence of a natural person or the principal place of business of a juristic entity.” The USPTO explained that that these rules we created to combat “the growing problem of foreign individuals, entities, and applicants failing to comply with U.S. law.”

Pamela Chestek, a well-known and highly regarded trademark practitioner, author and commentator, provided the address where she receives business mail: “PO BOX 2492, RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES 27602. Her website identifies a physical address of 300 Fayetteville St, Raleigh, NC 27601, which turns out to be the Raleigh, N.C. Post Office. This was not good enough for the USPTO, which could not sleep at night until it knew where Pamela slept at night.

On appeal, Chestek argued that the domicile address requirement was improperly promulgated for two independent reasons and that the Board’s decision enforcing the domicile address requirement should therefore be vacated. First, Chestek first argued that the USPTO was required to comply with the requirements of notice-and-comment rulemaking under 5 U.S.C. § 553 but failed to do so because the proposed rule did not provide notice of the domicile address requirement adopted in the final rule. Second, Chestek argued that the domicile address requirement is arbitrary and capricious

because the final rule failed to offer a satisfactory explanation for the domicile address requirement and failed to consider important aspects of the problem it purports

to address, such as privacy.

The Federal Circuit rejected Chestek’s first argument because § 553(b)(A) does not require the formalities of notice-and-comment for “interpretative rules, general statements of policy, or rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice.”

The Federal Circuit rejected Chestek’s second argument because the regulations were not arbitrary or capricious but were adopted the domicile address requirement as part of a larger regulatory scheme to require foreign trademark applicants, registrants, or parties to a

trademark proceeding to be represented by U.S. counsel. The Federal Circuit said that because the USPTO would need to know an applicant’s domicile address to determine if the U.S. counsel requirement applied, it reasonably required all applicants to provide their domicile address. The USPTO’s justification for all applicants to provide a domicile address is therefore at least reasonably discernable when considered in the full context of the U.S. attorney requirement and the decision to condition that requirement on domicile.

Fraudulent Section 15 Affidavit May Void Incontestability, but it Does Not Make Registration Invalid

In Great Concepts, LLC, v. Chutter, Inc., [2022-1212] (October 18, 2023), the Federal Circuit reversed the TTAB’s cancellation of Reg. No. 2929764 on the mark DANTANNA’S due to the filing of a fraudulent declaration by a former attorney for the registrant.

Registrant’s former attorney filed combined Section 8 and 15 Declarations, Affidavits declaring, among other things, “there is no proceeding involving said rights pending and not disposed of either in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office or in the courts.” This statement was false: as of March 2010, both the cancellation proceeding in the PTO and the Eleventh Circuit appeal from Mr. Tana’s district court action were still pending.

The issue for the Federal Circuit was whether Section 14 of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1064, permits the Board to cancel a trademark’s registration due to the owner’s filing of a fraudulent Section 15 declaration for the purpose of acquiring incontestability status for its already-registered mark. The Board has long believed it has such power, and it exercised such purported authority in the instant case. The Federal Circuit concluded that Section 14 does not permit the Board to cancel a registration:

Section 14, which allows a third party to seek cancellation of registration when the “registration was obtained fraudulently,” does not authorize cancellation of a registration when the incontestability status of that mark is “obtained fraudulently.”

Fraud committed in connection with obtaining incontestable status is distinctly not fraud committed in connection with obtaining the registration itself. The Federal Circuit said that the Board the Board may consider whether to declare that Great Concepts’ mark does not enjoy incontestable status and to evaluate whether to impose other sanctions on Great Concepts or its attorney.