In In re Detroit Athletic Co., [2017-2361](September 10, 2018) the Federal Circuit affirmed the TTAB’s affirming the Patent and Trademark Office’s refusal to register

DETROIT ATHLETIC CO. for sports apparel retail services.

The Trademark Examiner refused registration of DETROIT ATHLETIC CO. in view of a prior registration on DETROIT ATHLETIC CLUB. The TTAB affirmed, concluding that, “because the marks are similar, the goods and services are related, and the channels of trade and consumers overlap,” consumers are likely to be confused by the marks. The Board considered four of the thirteen duPont factors relevant: (A) similarity or dissimilarity of the marks; (B) similarity or dissimilarity and nature of the goods or services; (C) similarity or dissimilarity of trade channels; and (D) concurrent use without evidence of actual confusion.

On the similarity of the marks, the Federal Circuit found the TTAB’s finding that the marks “are nearly identical in terms of sound, appearance and commercial impression” was supported by substantial evidence. The Federal Circuit undertook a detailed analysis of the marks, finding that when viewed in their entireties, the marks reveal an identical structure and a similar appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression. The Federal Circuit rejected the argument that the difference between Co. and Club would allow consumers to distinguish the marks. The Federal Circuit said that while the mere fact that “Co.” and “Club” were disclaimed from their respective does not give one license to simply ignore those words in the likelihood of confusion analysis, the TTAB did not err in focusing on the more dominant portions of the marks. Moreover, the record showed that these terms did not serve source-identifying functions.

With respect to the similarity of the goods, the Federal Circuit agreed with the TTAB that while the goods and services are not identical, they substantially overlap, which weighs in favor of finding a likelihood of confusion. In response to applicant’s argument that consumers would have little problem distinguishing between DACo’s clothing store

and the Detroit Athletic Club’s private social club., the Federal Circuit said that the relevant inquiry in an ex parte proceeding focuses on the goods and services described in the application and registration, and not on real-world conditions.

With respect to trade channels, the Federal Circuit found that the Board’s determination that the Detroit Athletic Club’s clothing comprises the type of goods likely to be sold through applicant’s sports apparel retail services, was supported by substantial evidence. Applicant argued that the Detroit Athletic Club sells clothing only to its club members and only in its gift shop located onsite, and thus this would prevent confusion among the public at large, but the Federal Circuit found this too, irrelevant, because confusion must be evaluated with an eye toward the channels specified in the application and registration, not those as they exist in the real world. The Federal Circuit noted that to the extent applicant objects to the breadth of the goods or channels of trade described in the Detroit Athletic Club’s registration, that objection amounts to an attack on the registration’s validity, an attack better suited for resolution in a cancellation proceeding.

Finally, with respect to the lack of confusion during concurrent use, the Federal Circuit noted that the relevant test is likelihood of confusion, not actual confusion, so evidence

that the consuming public was not actually confused is legally relevant to the analysis, but it is not dispositive. Further, the Federal Circuit’s analysis of applicant’s evidence did not establishe a lack of consumer confusion in commercially meaningful contexts.

The Federal Circuit therefore concluded that substantial evidence therefore supports the TTAB’s finding that the evidence purporting to show a lack of actual confusion was not sufficiently probative.

On balance, the factors supported a finding of likelihood of confusion. The Federal Circuit rebuffed applicant’s argument that the Board erred by not addressing

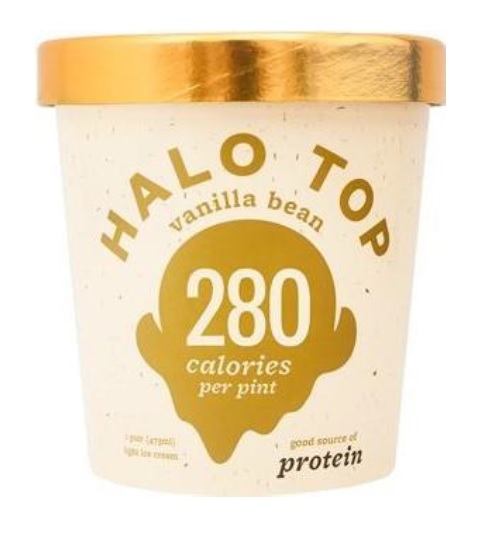

all DuPont factors for which evidence was proffered, noting that it is well established that the Board need not consider every DuPont factor. The Board is not required to expressly address each evidentiary item proffered by a party.

HBO alleges that the Botanic Garden’s use of GAME OF THORNS is likely to cause confusion:

HBO alleges that the Botanic Garden’s use of GAME OF THORNS is likely to cause confusion: